Gendler's Holistic Hypothetico-Deductivism: A Neglected Empiricist Account of A Priori Knowledge

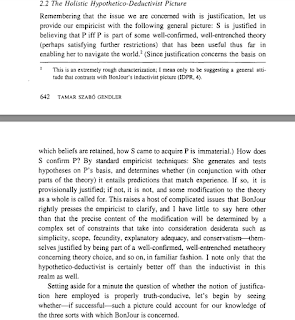

Gendler, Tamar. 2001. " Empiricism, Rationalism, and the Limits of Justification ", Philosophy & Phenomenological Research 6:3, 641-648. It's perhaps understandable that the paper is not very well known, as it was written as an invited reply piece for the PPR book symposium on Bonjour's 1998 In Defense of Pure Reason . Nonetheless, Tamar Gendler's brief defense here of holistic hypothetico-deductivism shows it to be a prima facie plausible, powerful account of (supposed) a priori knowledge available to the empiricist. Here are some snippets of the paper capturing a sketch of the view (click to enlarge): And here's a snippet that gives one a sense of how the story goes with (supposed) a priori truths: Here are a few snippets that give one a sense of how the story goes for deductive inference: Gendler also persuasively argues that the rationalist can do no better than the hypothetico-deductivist i...